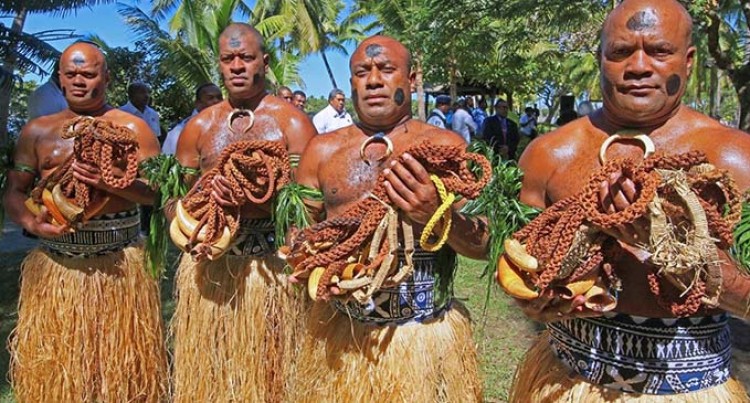

A tabua is a polished tooth of a sperm whale that is an important cultural item in Fijian society. They were traditionally given as gifts for atonement or esteem (called sevusevu), and were important in negotiations between rival chiefs.

Tucked inside a dark shopping plaza in this otherwise enchanting city in the South Pacific is Henry’s Pawn Shop. Inside, Joseph Baivatu, 29, prepares to make the next payment on a layaway for something very special: a large sperm whale tooth. Known as a tabua in Fiji, a sperm whale’s tooth is often given by a groom and his family to the parents of the man’s (hopefully) future bride when he asks permission to marry her.

“The whole of my life I want to be married, so I give my goods and my time,” said Mr. Baivatu, a Vodafone technician in Suva, Fiji’s capital and largest city. “I give the tabua, and that means ‘I love you’ from the inside.”

Mr. Baivatu, who is as soft-spoken as he is tall and broad shouldered, said he had yet to meet the future Mrs. Baivatu, but that detail does not get in the way. He is determined to be ready with tabuas when she turns up.

Tabua (pronounced tam-BOO-ah) roughly translates to “sacred” in Fijian. The valuable relic, associated with good luck and even supernatural powers, has traditionally paved the way for marriages in this nation of more than 300 islands.

Ta

With few countries still harvesting whales and laws limiting the international trade of endangered species like the sperm whale and their specimens, the number of tabuas circulating in Fiji is dwindling, causing prices to rise. A single tooth strung with braided cord as an oversize pendant on a necklace can cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars. Mr. Baivatu is aiming to buy 12 teeth, which he said would amount to three months of his salary.

Despite the cost, giving tabuas “is very much still alive and a part of our culture,” said Apo Aporosa, a New Zealand-based anthropology researcher with Fijian heritage. The practice is more common in rural areas, he said, but even in the urban areas, the tradition continues among some families.

Most noble families descended from chiefs keep a cache of tabuas available for when a son is in need. The modern-day romantics who choose to keep the tradition alive, however, often require a few trips to a pawnshop in a city center like Suva.

In addition to engagements, tabuas are given at weddings, funerals and births, and to seal an apology.

Tabuas “essentially communicate that the holder or presenter highly esteems the sanctity of the agreement, promise, etc.,” Simione Sevudredre, from the department in Fiji’s government that oversees indigenous affairs, wrote in an email.

During the days of warring tribes, before Fiji became a British colony in the late 1800s, if a chief wanted someone killed and was unable to do it himself, he offered a tabua to another tribe to take care of the matter. This was the case for an unfortunate 19th-century British missionary, the Rev. Thomas Baker.

According to national legend, the missionary offended a village chief, who then offered a tabua to another tribe to kill him. In 2003, the descendants of the village that killed — and promptly ate — Baker presented 100 tabuas to the missionary’s ancestors in an effort to break what was viewed as a curse on the area related to the death.

At a handicraft market in downtown Suva, Sarah Naviqa, a shopkeeper, sat in a tiny stall surrounded by mats, bags and fans woven from pandanus leaves. She plunked a blue plastic bag containing half a dozen sperm whale teeth on the table. Some were cream. Others had a brown hue. Their size varied from the length of a hand to the length of a forearm. The largest weighed about three pounds and cost about $1,000.

Buying a tabua ahead of an engagement is also about status, she said.

“It means the man’s family is quite well off,” said Ms. Naviqa, whose husband presented six tabuas to her family in 1970.

The parents gave their blessing for the marriage, but Ms. Naviqa said she had ultimately made the decision. “I was working and very independent,” she said.

Ms. Naviqa keeps a supply of tabuas available by buying them from families who run into financial troubles. “Once they get into financial constraints, that is when they have to sell these items,” she said. “Keep on recycling, eh? And very good business. The more recycling, the better for us.”

A fish specialist for a conservation nonprofit, Waisea Batilekaleka, 34, was recently heading back to Suva from a work trip on one of the many ferries that link the city with Fiji’s outlying islands. Mr. Batilekaleka said that during the time of his engagement and wedding in 2002, he had given almost 20 tabuas to his wife’s family.

Some he inherited from his family and others came from his mataqali, or clan. Mr. Batilekaleka also took three years to save for the four he bought himself. He gave his wife a diamond ring, which remains rare in much of Fiji.

Mr. Batilekaleka said that saving for the tabuas, which 15 years ago cost him about $150 each, had shown that he was “willing to take up this responsibility to become a husband and a father.”

Despite the value placed on tabuas, Fijians did not traditionally hunt whales. Instead, it was hunters from the neighboring island nation of Tonga who killed the whales and traded the teeth with the Fijians. That supply was cut off when Tonga banned whaling by royal decree in 1978.

Two decades later, Fiji signed a global treaty that restricted international trade in endangered species and their parts, including sperm whale teeth. A cultural exemption allows for the export of 225 tabuas each year, according to Sarah Tawaka, a senior environmental officer at Fiji’s Department of Environment. A special permit is required to bring sperm whale teeth into Fiji, Ms. Tawaka wrote in an email.

Enterprising Fijians have taken advantage of dead sperm whales that wash up on beaches. The jaw and teeth of a sperm whale found dead on Nukulau Island near Suva in 2015 were quickly taken, according to The Fiji Times. Dead sperm whales in Tonga faced similar fates.

Tabuas made from plastic are also circulating, according to sellers in Suva, who said they had ways to identify the fakes.

“You use matches to light the tabua,” said Rachel Turaga, 19, a shop assistant at Henry’s Pawn Shop. “If it melts, that’s the fake one.”

Source: Serena Solomon